Inducted on June 15, 1969

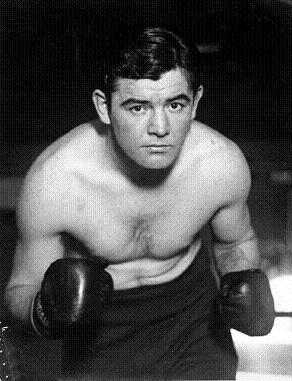

James Walter “Cinderella Man” Braddock (June 7, 1905 – November 29, 1974) was an American boxer who was the world heavyweight champion from 1935 to 1937.

Fighting under the name James J. Braddock (ostensibly to follow the pattern set by two prior world boxing champions, James J. Corbett and James J. Jeffries), he was known for his powerful right hand, solid chin and comeback from a floundering career. He had lost several bouts due to chronic hand injuries and was forced to work on the docks and collect social assistance to feed his family during the Great Depression. In 1935 he fought Max Baer for the Heavyweight title and won. For this unlikely feat he was given the nickname “Cinderella Man” by Damon Runyon. Braddock was managed by Joe Gould.

Early life

Braddock was born in Hell’s Kitchen in New York City on West 48th Street, within a couple of blocks of the Madison Square Garden venue, where he later became famous. He was the son of Irish-American parents Elizabeth (née O’Tool) and Joseph Braddock.[1] He stated his life’s early ambition was to play football for Knute Rockne at the University of Notre Dame, but he had “more brawn than brains.”

Career

Braddock pursued boxing, turning pro at the age of 21, fighting as a light heavyweight. After three years, Braddock’s record was 44-2-2 with 21 knockouts.[citation needed]

In 1928, he pulled off a major upset by knocking out highly regarded Tuffy Griffiths. The following year he earned a chance to fight for the title, but he narrowly lost to Tommy Loughran in a 15-round decision. Braddock was greatly depressed by the loss and badly fractured his right hand in several places in the process. His career suffered as a result, as did his disposition.[citation needed]

His record for the next 33 fights fell to 11-20-2. With his family in poverty during the Great Depression, Braddock had to give up boxing for a little while and worked as a longshoreman. Due to frequent injuries to his right hand, Braddock compensated by using his left hand during his longshoreman work, and it gradually became stronger than his right. He always remembered the humiliation of having to accept government relief money, but was inspired by the Catholic Worker Movement, a Christian social justice organization founded by Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin in 1933 to help the homeless and hungry. After his boxing comeback, Braddock returned the welfare money he had received and made frequent donations to various Catholic Worker Houses, including feeding homeless guests with his family.[citation needed]

Baer vs. Braddock

In 1934, Braddock was given a fight with the highly touted John “Corn” Griffin. Although Braddock was intended simply as a stepping stone in Griffin’s career, he knocked out the “Ozark Cyclone” in the third round. Braddock then fought John Henry Lewis, a future light heavyweight champion. He won in one of the most important fights of his career. After defeating another highly regarded heavyweight contender, Art Lasky, whose nose he broke during the bout on March 22, 1935, Braddock was given a title fight against the World Heavyweight Champion, Max Baer.[citation needed]

Baer hardly trained for the bout. Braddock, on the other hand, was training hard. “I’m training for a fight. Not a boxing contest or a clownin’ contest or a dance,” he said. “Whether it goes 1 round or 3 rounds or 10 rounds, it will be a fight and a fight all the way… When you’ve been through what I’ve had to face in the last two years, a Max Baer or a Bengal tiger looks like a house pet. He might come at me with a cannon and a blackjack and he would still be a picnic compared to what I’ve had to face.”[2]

Considered little more than a journeyman fighter, Braddock was hand-picked by Baer’s handlers because he was seen as an easy payday for the champion. Instead, on June 13, 1935, at Madison Square Garden Bowl, Braddock won the Heavyweight Championship of the World as the 10-to-1 underdog in what was called “the greatest fistic upset since the defeat of John L. Sullivan by Jim Corbett“.[3]

During the fight, a dogged Braddock took a few heavy hits from the powerful younger champion (30 years vs 26 years for Baer), but Braddock kept coming, wearing down Baer, who seemed perplexed by Braddock’s ability to take a punch. In the end, the judges gave Braddock the title with a unanimous decision.[4]

Heavyweight Champion

James Braddock suffered from problems with his arthritic hands after injuries throughout his career, and in 1936, his title defense in Madison Square Garden against the German Max Schmeling was canceled under suspicious circumstances. Braddock argued he would have received only a US$25,000 purse against Schmeling, compared to $250,000 against rising star Joe Louis. There was also concern that if Schmeling won, the Nazi government would deny American fighters opportunities to fight for the title.[5] Finally, American commentators had expressed opposition to the fight in light of the connections between Schmeling and Adolf Hitler, with whom the German fighter had been associated after his earlier victory over Louis.[5][6]

Louis was considered to be the more dangerous opponent and the fact that he, being a black man, could be heavyweight champion made many boxing insiders against his getting a title shot. Braddock agreed to the fight with the stipulation that he would receive 10% of promoter Mike Jacobs’ future fights. So if Braddock beat Louis or Louis retired, the deal was for any fight and any boxer that Jacobs was handling for the next ten years. This money did not include the purse, just money from the concessions i.e. hotdogs, drinks, tee shirts programs etc. So win or lose Joe Gould got Braddock a great deal. Braddock was able to knock down Louis in the fight, but Louis went on to win, knocking Braddock out for the first and only time in his career. Louis was quoted as saying that Braddock was the bravest man he ever fought.[citation needed]

Personal life

Braddock married Mae Fox in 1930 and the couple had three children, James (Jay), Howard and Rosemarie. He enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1942 and became a 1st Lieutenant. Upon return, he worked as a marine equipment surplus supplier and helped construct the Verrazano Bridge in the early 1960s.[7]

Death and legacy

James J. Braddock North Hudson Park in North Bergen, New Jersey.

On his death in 1974 at the age of 69, James J. Braddock was interred in the Mount Carmel Cemetery in Tenafly, New Jersey. He was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 2001. James J. Braddock North Hudson County Park in North Bergen, New Jersey is named in his honor.[8]

The 2005 biographical film Cinderella Man tells Braddock’s story. Directed by Ron Howard, it stars Russell Crowe as Braddock and Renée Zellweger as his wife, Mae.[9] The film had an estimated budget of $88 million and grossed $108.5 million worldwide.[10] Crowe’s performance earned him a Golden Globe nomination for Best Actor. Paul Giamatti, playing Braddock’s manager Joe Gould, was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor. The role of neighbor Sara Wilson was played by Rosemarie DeWitt, who is Braddock’s real-life granddaughter (daughter of Braddock’s daughter Rosemarie Braddock and husband Kenny DeWitt). The film received mostly positive reviews.[11]

University of Michigan Football coach Lloyd Carr used Cinderella Man to inspire his team during their 2006 season.[12]

Another Story:

Career Overview

Like the man himself in the 1930s, the legacy of Jim Braddock has had a recent comeback. The 2005 motion picture “Cinderella Man” revived his forgotten name and story to people of today. Although the film romanticized some of the everyman appeal of Braddock’s story, and unfairly demonized his opponent Max Baer as the movie’s villain, the tale of his journey from impoverished dock worker to owner of the richest title in sports is compelling. Overcoming the starvation and destitution of the Depression, chronic injuries to his right hand, and twenty-three professional losses inside of five years through determination and hard work, Braddock’s story represents one of the great aspects of the sport of boxing: its presentation of opportunity to the apparently hopeless and its occasional rewarding of hard work over natural talent. Which is not to say that he lacked talent. Fast and skilled, Jimmy showed skill as a boxing counter puncher. Possessed of a thunderous right hand punch and known as a determined competitor, Braddock suffered just two knockout losses in eighty-six pro outings. On top of that, he fought eight bouts against hall of fame competition and etched himself a place in the hall over a twelve year career.

Bulldog of Bergen

Though Braddock’s winning the heavyweight championship was a major upset, it was not as though he came out of nowhere. Jimmy had been a valid contender in the light heavyweight division earlier in the decade. Born James Walter Braddock into the notoriously impoverished Irish American neighborhood of Hell’s Kitchen in New York City, Jimmy’s earliest experience with fisticuffs occurred in the streets at a young age. After he moved with his parents to North Bergen, New Jersey as a schoolboy, his fighting ways continued until someone suggested he channel his violent habits into organized boxing. At age sixteen, Jimmy began his amateur career. After winning the New Jersey State championships in both the light heavyweight and heavyweight divisions, he eventually turned professional at twenty years old.

Braddock’s manager, Joe Gould suggested that Jimmy change his name, from James Walter Braddock to “James J. Braddock”, for stage purposes. The “J” initial was to imitate the frequently used middle initial of early heavyweight boxing champions James J. Corbett and James J. Jeffries. Gould guided his new charge into his first pro match against Al Settle at Union City, New Jersey, in 1926. The fight went the scheduled four round distance and, because official boxing decisions were illegal in New Jersey and other states at the time, the fight was official listed as a “no-decision”. It was a lackluster start for Gould’s new light heavyweight fighter, but Jimmy quickly showed promise in the next several months, knocking out his next eleven opponents, eight in the first round. By the end of the year he was fighting regularly in New York City, where the big money opponents and crowds appeared. He made a successful debut at Madison Square Garden on January 28, 1927 against George LaRocco. Though LaRocco outweighed him by twenty-two pounds, Braddock put him away inside of a round.

With Braddock still undefeated by the end of 1927, Gould began making a serious push at getting his fighter a title shot in 1928. A decision loss to the bigger Joe Monte over ten rounds on June 7 of that year, Jimmy’s first professional loss, did not discourage he or Gould. Braddock was put in the ring with marginal contender Joe Sekyra just three bouts later, Sekyra taking a ten round decision. By this point, the newspapers had begun worrying that Braddock’s talent was being squandered by Gould, who was rushing him too quickly to the top. Ignoring the critics, Braddock next took on Pete Latzo, the former welterweight champion who was making a comeback as a light heavyweight. The result was a noteworthy upset, as Jimmy broke the ex-champ’s jaw and earned a ten round decision victory. That essential victory having saved his status as a young prospect, Braddock was nonetheless a significant underdog when he next fought undefeated power-puncher Tuffy Griffith at Madison Square Garden. To the astonishment of all in attendance, Braddock dropped his man four times in the second round for a sensational knockout win.

At the close of 1928, The Ring, the sport?s most popular journal, rated Jimmy as the number one contender for the crown held by world light heavyweight champion Tommy Loughran. On January 18, 1929, he was matched with the number two ranked contender, Leo Lomski of Aberdeen, Washington. Lomski took the ten round decision, but Braddock quickly rebounded with a ninth round stoppage of former world champion Jimmy Slattery, two months later. After a first round pummeling of overmatched Eddie Benson in April, Braddock was finally given his shot at Loughran. A future hall of famer considered among the great light heavyweight champs in history, Loughran was a fast, skilled boxer, who was by this time already a veteran of over one hundred pro bouts and was making his fourth defense of the championship. On July 18, 1929, he danced circles around the relative upstart Braddock, dealing the New Jersey fighter an embarrassingly one-sided boxing lesson and taking a fifteen round unanimous decision.

Financial & Professional Troubles

He was in the ring less than a month later to fight the unknown Yale Okun in Los Angeles. The upset decision in favor of Okun, however, foreshadowed the tailspin Braddock’s career was about to take. At the same time, the loss illustrated that Braddock appeared to have lost confidence due to the loss to Loughran noted above. On November 15, 1929, looking to prove the doubters wrong, Jimmy took on number one contender Slapsie Maxie Rosenbloom, another future hall of famer and more experienced fighter. Rosenbloom won a decision, dealing Jimmy his third consecutive loss in a period of four months.

Braddock’s boxing career took another turn for the worse when he was forced to work on the docks (due to the effects of the 1929 stock market crash and the Great Depression) and did not have the time to train or money to pay trainers. His right hand, his best punch, also frequently broke in fights and Jimmy did not have the money to get it properly cared for. Instead he would often go into fights on short notice, just days apart, disguising the injury. From January, 1930 to May, 1933, he lost seventeen pro bouts and disappeared from the view and minds of the boxing press and fans. He moved into the heavyweight division, but fared no better. With fight offers now coming less frequently and respectable paydays even less frequently than that, Braddock reluctantly borrowed from welfare to support his children. Things seemed to be turning up for Jim’s career in the Summer of 1933. He won two consecutive bouts in June and July. But after breaking his right hand in a bout against prospect Abe Feldman on September 25, Braddock’s career seemed over. Unable to fight and only working occasionally on the Hoboken docks, Jimmy’s future seemed bleak.

Cinderella Man

Now living in horrendous poverty, Braddock was suddenly open to a return to the ring when Madison Square Garden promoter James J. Johnston approached him about facing Corn Griffin, Johnston’s latest prospect. Griffin had impressed sportswriters with his boxing technique as a sparring partner to reigning heavyweight champion Primo Carnera. On two day’s notice, a match was made between Griffin and Braddock, who was perceived as a has-been pushover for Giffin to annihilate, on the under card of the heavyweight championship bout between Primo Carnera and Max Baer at the Garden on June 14, 1934. The younger, fresher Griffin fearlessly battered his over-the-hill opponent in the opening round, and sent Jimmy down for the second time in his career during those second round. Jimmy rose and stunned the crowd by putting Griffin down with a well-time right hand counter. The remainder of the round was all Braddock, as Griffin, clearly stunned, flailed aimlessly and took big right hand blows to the head. The fight continued along the same lines going into the third, until the referee stopped the match and declared Jimmy the upset winner. “I did that on hash”, Braddock gloated to Gould in victory. “Wait till you see what I can do on steak.” Jimmy’s purse for the bout was two-hundred and fifty dollars.

While Griffin had been no top contender, the surprising win did convince some that Braddock may have enough left to continue fighting. When Madison Square Garden’s Jimmy Johnston signed up-and-coming light heavyweight John Henry Lewis of Pheonix, Arizona to a three-fight contract, Johnston arranged for Lewis to face Braddock in what was supposed to be a showcase for Lewis in his New York debut. Two years earlier, the slick and swift Lewis won a clear cut ten-round decision over Braddock and was the heavy favorite for the rematch on November 16, 1934. Again Jimmy turned the tables. He outfought his younger opponent, even putting Lewis down. After ten rounds, Braddock was the winner and took the ten round decision. John Henry Lewis would go on to win the world’s light heavyweight championship and establish credentials as a future hall of famer.

Now a surprise entry into the heavyweight contender rankings, Braddock was matched with fellow contender Art Lasky of Minneapolis. Lasky was being groomed for a title shot at heavyweight champion Max Baer, but needed a win over a name opponent in order to secure his chance. When they got into the ring together on March 22, 1935, at Madison Square Garden, Lasky outweighed Braddock by nearly fifteen pounds. Braddock, however, turned his size disadvantage into an advantage. He constantly circled the heavier man, using his work rate and punching accuracy to maintain a lead on the scorecards and keep Art from getting settled. In the eleventh round, Lasky managed to land a terrific punch that sent Jimmy’s mouthpiece flying. But otherwise, the fight was all Braddock and, after fifteen rounds, the outcome was clear.

Braddock’s 1934 to 1935 comeback had created a sensation in fight circles. Damon Runyon dubbed him the “Cinderella Man” because of his rags-to-riches story and The Ring magazine now rated him as the number two heavyweight contender, behind Germany?s Max Schmeling. When the Madison Square Garden Corporation, who virtually controlled the heavyweight championship at the time, demanded Schmeling face Braddock to determine who would get a chance at Max Baer?s title, Schmeling outright refused to fight Jimmy. As a result, Garden executives arranged a title shot for Braddock. Younger and much bigger, the hard-hitting, wild-brawling Baer came into the fight the favorite by eight-to-one. However, Max failed to take his challenger seriously and neglected to train properly for the match. On June 13, 1935, at Madison Square Garden, the champion found himself having an unexpected tough time. Braddock, meanwhile, fought the fight with determination and skill. He used constant movement and a stiff left jab to keep Max unsettled. Baer tried to throw his haymaker right hand, but Braddock knew to look out for it and the champion usually missed by a long distance. Unable to compete with Braddock’s conditioning and technical precision, Baer could do little else but gasp for breath and make faces at his opponent. The champion fouled on occasion and, when warned by the referee, made theatrical gestures of apology to the crowd and Braddock. The result was a unanimous decision for Braddock in one of the great upsets in the annals of the heavyweight championship. In two years, Jim Braddock had gone from living off of government assistance to capturing the richest prize in sports.

The Louis Fight and Later Years

Jimmy and manager Joe Gould sought to make the most of the newfound fame and success. For two years, Braddock avoided professional competition. Instead, they froze the title, which allowed Braddock to earn money touring the country giving boxing exhibitions and public appearances. When it came time for him to return to the ring, Max Schmeling was still the standout heavyweight contender. A former champion himself and a future hall of famer, the German had recently scored his own upset victory of note by knocking out the undefeated Brown Bomber of Detroit, Joe Louis, in twelve rounds. Though the recent political activities inside Schmeling?s native country promised controversy surrounding an international title bout, arrangements for a Braddock-Schmeling fight were put into the works by Jimmy Johnston and the Madison Square Garden Corporation. When Braddock claimed a hand injury in training, however, those plans were postponed. Whether or not the champ truly suffered the injury is not known for sure, but the delay allowed Gould time to weasel out of the Schmeling match. Mike Jacobs, promoter for the Twentieth Century Sporting Club (the Garden?s top rival), offered Gould ten percent of all of the ring earnings of Joe Louis for the next decade if Braddock would sign to fight Louis instead. Over the vehement protests of Schmeling and the Garden, Braddock signed to face Louis for the championship.

The Louis fight, held at Chicago’s Comiskey Park on June 22, 1937, was Jimmy’s first in two years. His challenger, nine years his junior, had fought a dozen times in that period, winning eleven of those bouts, ten by knockout. In a rare case of the challenger being the favorite over the champion, Louis was made the 10-to-1 favorite. At first, it appeared that Jimmy would pull off the upset. In the first round, he fired a short right hand that put Louis on the seat of his pants. Stunned but not hurt, Louis rose at the count of two and dealt a brutal beating to the champion. Jimmy did well to last into the eighth round, when a right hand caught him directly on the chin. Braddock’s knees sagged and then, with a delayed reaction, he crumbled to the floor, blood spilling out of his nose onto the floor. He was counted out and the title transferred to Louis.

Feeling he had enough in the tank for one more win, Jimmy next fought on January 21, 1938. His opponent, Welsh Tommy Farr, was a clever boxer who had gone fifteen rounds in a losing title shot at Louis. Again Braddock scored a noteworthy upset, rallying in the later rounds to take a ten round decision. With that, Jimmy retired, focusing instead on a career as a manager of younger fighters. He invested the money won in his comeback well and ran several successful business in later life. He passed away on November 29, 1974 at age 69 and was inducted posthumously into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 2001. Four years later, he legend was revitalized with the biopic “Cinderella Man””, with Russell Crowe playing the role of Jim.

Sources

- Bak, Richard. Joe Louis: The Great Black Hope, 1998.

- Fleischer, Nat. The Heavyweight Championship., 1961.

- Hague, Jim. Braddock: The Rise of the Cinderella Man, 2005.

- Schaap, Jeremy. Cinderella Man: James Braddock, Max Baer, and the Greatest Upset in Boxing History, 2005.

Cinderella Man: James Braddock, Max Baer, and the Greatest Upset in Boxing History

Factoids

Inducted into the following Halls of Fame:

- Ring Magazine Boxing Hall of Fame (1964)

- New Jersey Boxing Hall of Fame (Inaugural Class of 1969)

- International Boxing Hall of Fame (2001)

- World Boxing Hall of Fame

Braddock reportedly fought a 4-round pro fight under the name Jimmy Ryan in 1923, before he started his amateur career.

Further Reading and Media

- His story is featured in the 2005 movie Cinderella Man and Cinderella Man: The Real Jim Braddock Story a documentary from the makers of the movie, with contribution from Mike DeLisa (see below).

Books include:

- Cinderella Man by Mike DeLisa

- Cinderella Man: James Braddock, Max Baer, and the Greatest Upset in Boxing History by Jeremy Schaap

External Links

- Official Homepage

- CBZ Braddock Page

- Gravesite

- Braddock Fought Best as Odds Favored Foes, The Milwaukee Journal, June 20, 1935

- Lessons in Manliness: James J. Braddock, by Brett & Kate McKay on August 25, 2009 [1]

- Jim Braddock Through With Ring Forever, Associated Press, January 31, 1938, by Hugh S. Fullerton Jr. [2]

- Quits Docks To Win Three Great Fights: Half Starved, Braddock Battles His Way To Scrap With Baer, by Harry Grayson, Sports Editor, NEA Service, June 5, 1935 [3]

- Jim Braddock Tribute [4]

Boxing Record: Jim Braddock