Inducted on October 29, 1982

THE ODYSSEY OF BENNY RUBIN – By CHUCK TRIBLEHOBN

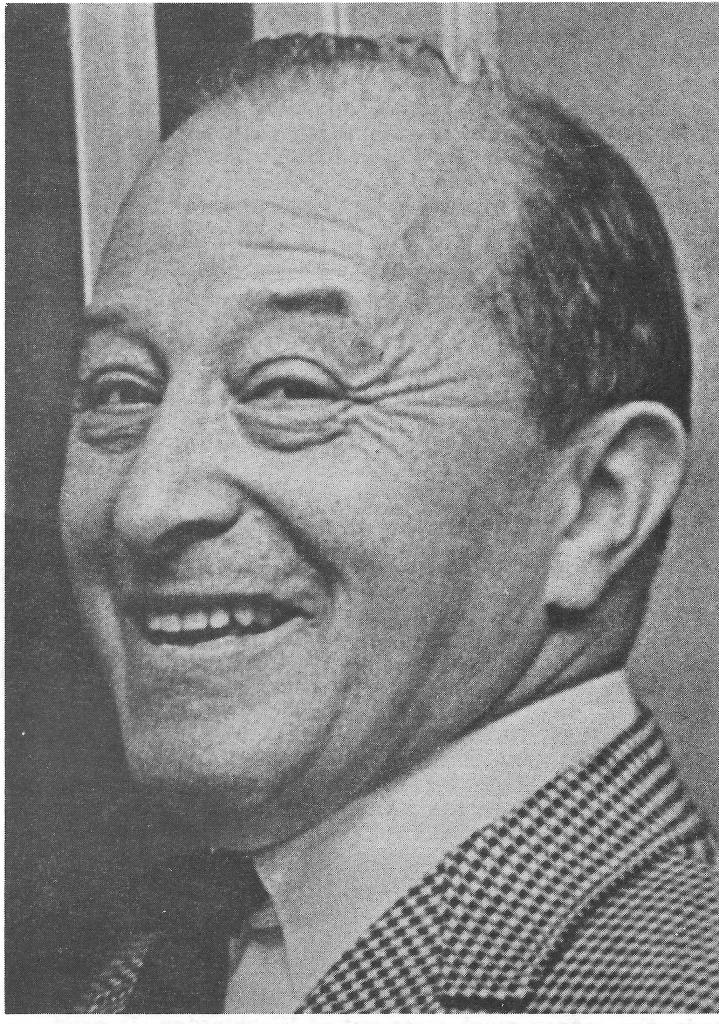

“I’ve always been a promoter at heart,” says Benjamin “Benny” Rubin, co-owner of the Greenbrier Restaurant, Route, 1, North Brunswick, New Jersey. Rubin, a 5-foot, 2-inch bundle of dynamic energy, and partner John Moran have teamed to make the Greenbrier one of the most successful dining establishments in the state.

“I’ve always been a promoter at heart,” says Benjamin “Benny” Rubin, co-owner of the Greenbrier Restaurant, Route, 1, North Brunswick, New Jersey. Rubin, a 5-foot, 2-inch bundle of dynamic energy, and partner John Moran have teamed to make the Greenbrier one of the most successful dining establishments in the state.

But it wasn’t always this way for the New Brunswick native who started out working in his father’s grocery store.

Always an engaging personality, Rubin used every inch of his small frame (It’s a talking piece.”) as a fight promoter in the late 1930s and throughout the 1940s.

A strong supporter of boxing clubs, Rubin made Highland Park’s old Masonic Temple – destroyed by fire a few years ago – the launching pad which sent several ring greats to the big time.

Rubin lists Rocky Graziano, Sandy Saddler, Ike Williams, Joe Baksi and Joe “Butch” Lynch, the last a local product, among the boys to whom he gave a start in the squared circle. In fact, little Benny booked Graziano’s first professional bout in the Highland Park arena in 1944.

“I predicted at that time that Rocky would become champion,” says Rubin proudly. He also foresaw the future for Williams, long-time lightweight king whose first 10 fights Rubin booked. Although he did not manage Williams, Benny advised him during his club fighting days.

Rubin, whose only higher education after attending New Brunswick public schools, consisted of correspondence courses and a part-time stint at Drake Business College, lists Irving Cohen and Teddy Brenner among the prominent non-boxers who have gone on to make a name in the game since working with him. Brenner, of course, is the Madison Square Garden matchmaker whose most recent success was the spectacular Nino Benvenuti-Emile Griffith, Joe Frazier-Buster Mathis doubleheader which introduced the sport to the new Garden.

“He (Brenner) got his start working in my office,” relates Rubin, who opened up gyms and staged boxing shows throughout Central New Jersey.

Rubin is full of tales about his unique career as a fight promoter. He admits the catalog is endless and would take several evenings of casual conversation to touch upon half of them.

One anecdote concerns the gymnasium he established at Camp Kilmer during World War II.

“I wanted to give the boys something,” says Rubin, “so I opened a beautiful gym for them, fully equipped. They seemed to enjoy it.”

Enjoy it, they did; so much that one unit shipped off to Africa with all the equipment included among the baggage.

“I really didn’t mind, though,” Rubin says with a smile. “Gyms where the boys could be taught boxing were my contribution to the war effort.”

Rubin also is credited with staging the first Army-Navy relief show for the benefit of the troops during the war, a few years after he promoted a Milk Fund bout. The latter event was washed out by rain the first time around, but Benny, the little man with the big heart, rescheduled the bout at this own expense. He felt he owed it to his patrons.

One of the most energetic promotions involved the rise of Baksi as a heavyweight contender. Standing next to the big fighter during their trips around the country earned diminutive Benny the title of “Little Napoleon,” and a Baltimore Sun sports cartoonist depicted him as ‘Such. Baksi gained a crack at the title, but a fellow named Joe Louis blocked his path to the crown.

Middleweight Lynch also was a championship threat, says Benny, who took the New Brunswicker to Chicago for a training bout with slick Homer Williams. Lynch, according to Rubin, had Williams licked for seven rounds before a knockout punch by the latter leveled him in the eighth round.

“Little Napoleon,” though anything but a dictator, experienced setbacks in his tenure as a boxing promoter, but never really met his Waterloo. Pride in giving so many fighters their starts is tucked away in his personality even today, but little money went into his pocket during those early days.

Once, Rubin wanted to shed his promoter’s hat for lack of money, but the late Elmer Boyd, owner and publisher of the Daily Home News, stepped in, urging him not to throw in the towel. Civic-minded citizens and sports writers, who wanted something to write about, felt Rubin’s clubs and boxing were an important part of community life.

Boyd offer to subsidize Rubin’s fights. “Funny thing,” says Benny, “that’s just about the time I began to make money, so I really didn’t need him.”

Again, as predicted by Rubin, the advent of TV in the late ’40s brought the decline of club boxing, and his career as a club promoter went out with it. After the war Benny staged wrestling shows at the Masonic auditorium, and more recently he promoted closed-circuit television hookups in theatres for the big fights.

Occasionally, Rubin still is contacted at his restaurant by ex-fighters, interested backers, and ring potentials. They come for help and advice, hopeful of Benny’s support, but the likable 50-year-old is now a quality restaurant owner first. He questions the future of boxing, but admits he again could become interestedif the right boy come along. “Either they have it, or they don’t,” he says.

If there is any hope in the sport at all, it must be revived on the community-club level, ‘Rubin believes. “It must be subsidized nationally,” he adds. “In other words, the money must come out of Washington. It must be fed into municipalities to set up clubs for teaching and shows.

Benny feels a national boxing director is needed, and his personal choice is Abe Greene. Jack Dempsey is ‘also mentioned for the position, should it ever be established.

Promotion (what else?) also started Rubin up the long, often uneasy road to his present role as “host with the most” at the Greenbrier.

While promoting his fights and working at the grocery store, Rubin opened up a night spot in 1942 on the present site of the Greenbrier. It was known as the Rainbow Inn, featuring live entertainment.

While promoting his fights and working at the grocery store, Rubin opened up a night spot in 1942 on the present site of the Greenbrier. It was known as the Rainbow Inn, featuring live entertainment.

Here’s another field in which Rubin gave future stars their starts. He numbers Patti Page, Rosemary Clooney, Jill Corey, Buddy Hackett and Bob Eberle, among those who performed at his club, lived on the second floor of his building during their stands and earned a meager $50 a week for their efforts on the Rainbow Inn stage.

“I also take pride in having been able to give these entertainers a start,” says Benny, almost popping his buttons and chewing on an un-lit cigar. Rubin smokes, but rarely inhales, and is a non-drinker,

“I get a big kick out of switching the TV dial from ‘station to station to see these stars who worked for me in the old days, appearing on shows like Johnny Carson and Merv Griffin.”

Grocery store . . . boxing . . . entertainment . . . “I didn’t make any money in any of them,” says Benny.

Then one day about 10 years ago John Moran walked through the door of Benny’s place.

“It was a stroke of luck,” says Rubin. “I had turned the night club into a restaurant, but, knowing nothing about the business, I just couldn’t get it off the ground.”

Moran, who Benny calls a “dedicated restaurateur,” knew the business. He had worked for the established Mayfair Farms in North Jersey before starting a pie distributing company. The Iater venture was unsuccessful, and John came to Benny to collect on a baking bill. A partnership was quickly formed.

“He saw a future in the area for a quality restaurant,” says Rubin. “We scraped some money together, primarily from a prominent group of local industrialists and we were on our way.”

Moran’s knowledge mixed well with Rubin’s ability as a genial promoter and hand-shaker, and the combination has lifted the Greenbrier to the pinnacle it now enjoys. From 1958 on it gradually built up a reputation for fine food, service and atmosphere. For the past five or six years the establishment has been booked at least a year in advance for large parties, weddings and banquets.

Rubin is perhaps Moran’s number one admirer, but Benny’s family stands foremost in his life. He describes his wife, Sarah, as a . “tolerant” mother and mate. “After all,” he says, “she stood with me during those lean years as a boxing promoter and night club owner. Now we have a good thing going for us; now is the time to ‘sit back’ and make some money.”

The Rubins, who reside at 12 Reed Court, in New Brunswick, are the parents of two boys: Frank, a resident of Piscataway, a New Brunswick attorney; and steve, a student at Seton Hall Law School, who plans to follow in his brother’s footsteps. Benny and Sarah have two grandchildren.

The admiration which his patrons hold for “Litt>1e Napoleon” is reflected in the number of honors that have come his way.

Testimonials, among others, have been dealt out by the Middlesex County Catholic Youth Organization, who granted him an honorary membership (isn’t that an oddity for a little Jewish boy?”); the sports writers, who awarded a special citation (“I wasn’t even there, I was in Florida, so they gave it to me post-whatever-you-callit.”), and the North Brunswick Democrats (“And I’m not even politically inclined! It’s better that way.”).

“I just don’t understand these awards,” says Rubin.

“They are giving me the business, and then they are thanking me yet.”

Their answer . . . is that Benny Rubin is just a nice guy.