Inducted on June 15, 1969

Career Overview

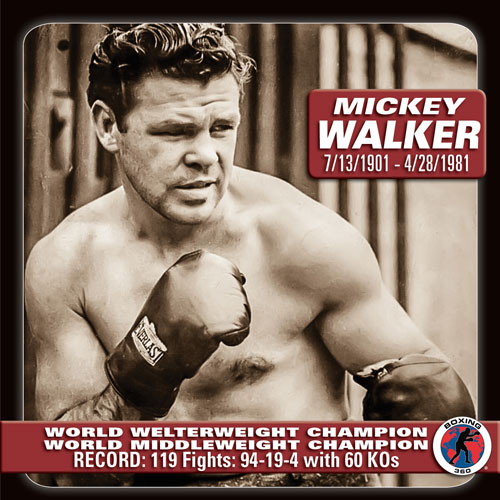

The only welterweight champion to ever become a successful contender in the heavyweight ranks, Mickey Walker was one of the bravest, toughest, and most popular boxers of his generation. A rugged scrapper with little use for ring technique or proper conditioning, Walker had tremendous success with his unpolished warrior’s style. A two-division champion whose title reigns spanned nine years, he defeated five hall of fame opponents over his sixteen year career and also emerged victorious in ten matches against opponents who outweighed him by twenty pounds or more. He is routinely rated by historians as one of the greatest welterweights and middleweights in history, and was also a fine performer at both light heavyweight and heavyweight. Writers of the age constantly marveled at his small stature but superhuman toughness. Hence his entirely appropriate nickname, the “Toy Bulldog.”

Welterweight

Born Edward Patrick Walker in Elizabeth, New Jersey on July 13, 1901, Walker’s father was a friend of legendary bare-knuckle boxing champion John L. Sullivan. His father was allegedly a talented fighter in his own right, though he never fought professionally. When he learned that Mickey, as Edward was called since birth, intended to become a boxing champion like Sullivan, the senior Walker was very upset. Despite his father’s objections, Mickey became a prizefighter while still a teenager, entering a local boxing competition in 1919 against a fellow by the name of Dominic Orsini. Walker was paid ten dollars for his work. Because official boxing decisions were outlawed by New Jersey state law at the time, the fight ended in a no-decision, as did many of Walker’s early contests. Because he had no formal boxing training, nor any amateur boxing experience, Walker was a crude sort of fighter from the start, but he packed a punch and relied upon sheer aggression to often overwhelm opponents. Losing just twice in his first forty contests, all fought in New Jersey within just over two years’ time, Walker secured himself a non-title fight with reigning welterweight champion Jack Britton. On July 18, 1921, Mickey took the champion the scheduled twelve round distance, but the more experienced Britton appeared to get the better of the action. Because the fight was held in Newark, New Jersey, the official result was a “no decision,” saving Walker from an official blemish on his record. Still, taking a veteran titleholder like Britton the distance was an impressive feat for an unknown kid from New Jersey who had only just passed his twentieth birthday.

Now a legitimate welterweight contender, Walker garnered fights with a range of respected contenders, including Dave Shade and Artie Bird, both of whom he knocked out, securing his chance for a second shot at Britton. This time the fight took place at Madison Square Garden in New York, with the world championship on the line. On November 1, 1922, Walker scored a knockdown in the twelfth and secured himself the fifteen-round decision and his first world title at the tender age of twenty-one. Thereafter, Walker campaigned mostly as a middleweight, only dropping back down to welterweight to make the occasional defense of his championship. In March of 1923 he defended the title for the first time against Pete Latzo in a no-decision bout in Newark. A few months later, in his second defense, against Jimmy Jones, the referee stopped the fight claiming neither fighter was trying to win. Though Walker later claimed to have suffered hand injuries that precluded him from using his typically aggressive style, the New Jersey Commission suspended his boxing license for a year.

Thus Walker was unable to defend the championship again until June 2, 1924, when he fought future Hall-of-Famer Lew Tendler over ten rounds in Philadelphia. Tendler was a veteran of more than one hundred fights who had twice fought for the lightweight championship. A crafty southpaw with a decent pop in his fists, Tendler gave the Toy Bulldog plenty of trouble. Walker managed to stay far enough ahead on the score cards, however, to secure himself a unanimous decision in his favor. A knockout of unheralded Bobby Barrett followed four months later. This continued success attracted world famous boxing manager Jack “Doc” Kearns, former manager of the reigning heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey. Walker and Kearns would become great friends and rumors of their escapades bouncing from whorehouse to bar and back to the whorehouse spending Walker’s money quickly became the talk of boxing circles.

Kearns helped Walker secure two key title shots in 1925. On January 7, 1925, Walker took on Ireland’s Mike McTigue for the light heavyweight championship. Amazingly, Walker entered the ring weighing less than 150 pounds. Outweighed by more than ten pounds, he nonetheless seemed to be in control of the fight. But he was unable to knock McTigue out and the fight lasted the scheduled twelve round distance, resulting officially in a “no decision” and McTigue’s keeping the title. On July 2, Walker took on middleweight champ and another future Hall-of-Famer Harry Greb in New York. Like Walker, Greb was an unschooled, rough-and-tumble brawler who often neglected training and was known for his wild lifestyle. The Ring magazine still recognizes Greb, nicknamed the “Human Windmill,” as the single greatest middleweight in history to this day. In front of 60,000 spectators he and Walker put on one of the fiercest and bloodiest championship battles of the century. Walker fought bravely and won several early rounds, but Greb firmly established his dominance by the closing rounds. Exhausted by his own early output and unable to compete with Harry?s constant work rate and hand speed, Walker took a terrific beating in the final minutes of the match but managed to stay on his feet to hear the closing bell. The decision, however, went to Greb, although Damon Runyon reported this fight as being close, with Walker out-fighting Greb in the fifteenth. Later that night the pair ran into each other at a local pub and the fight continued in a back alley. The impetuous Walker emerged victorious by sucker punching Greb, who was still removing his coat.

Undaunted by the loss to Greb, Walker continued to defend his welterweight championship, doing so successfully against Dave Shade and Sailor Friedman before losing it to Pete Latzo on May 20, 1926. Latzo was a tough customer and a talented boxer, who used movement to confuse Walker. Walker employed a constant body attack, but to no avail. Latzo, according to the New York Times, “won decisively simple,” and took a majority decision. Just over a month later contender Joe Dundee stopped Walker on cuts in the eighth round. Dundee, according to ringside reporters, repeatedly head-butted Walker to open the cut, but was inexplicably not punished by the referee.

Middleweight and Light Heavyweight

Winning his next three bouts, Walker managed to secure himself a second shot at the middleweight title, now held by Tiger Flowers, who had beaten Harry Greb and become the first African-American to hold the title. This bout between two future hall of famers took place at the Coliseum in Chicago, Illinois, before 11,000 spectators on December 3, 1926. In the early rounds, Flowers clearly took the lead by using his superior boxing skills against Walker. Cut and bleeding badly by the fourth round, Walker fell behind badly but continued to apply constant pressure and throw punches, most of them missing. In the final few rounds, however, the hunter finally began to get to his prey. He staggered the champion on multiple occasions and scored a flash knockdown in the ninth. Still, when referee Benny Yanger, the sole judge of the fight, awarded his decision to Walker, the arena erupted with boos and accusations of a fix. The Illinois Commission investigated but could find no evidence of dishonesty in the referee, confirming Walker’s status as the new middleweight champion.

Walker defended the championship twice in the next two years, first against England’s Tommy Milligan (a tenth round knockout) and Minnesota’s Jock Malone (a ten round no-decision). He was now earning bigger purses and greater challenges by making forays into the light heavyweight division. He won a 1927 rematch with Mike McTigue via first round knockout and then battered former champion Paul Berlenbach over ten rounds just three weeks later. On March 28, 1929, Walker took on reigning light heavyweight champ Tommy Loughran for that title at Chicago Stadium. By now all of the hard living and hard fights were getting to the Toy Bulldog, who could not compete with Loughran’s combined size, speed, and skills. He lost a ten round decision, but showed some of his old form in whipping light heavyweight contender Leo Lomski and middleweight contender Ace Hudkins (in defense of his middleweight title) in the next few months. At the end of 1929, Walker abandoned his middleweight championship, stating his intention to go after the biggest prize in sports, the heavyweight championship of the world.

Heavyweight

Twice beating aging heavyweight contender Johnny Risko in 1930 and 1931, Walker surprised many by establishing himself as a potential threat among the big men. Even more astonishing was his win over the monstrous Bearcat Wright, who, according to one source, stood over a foot taller than Walker and outweighed him by 100 pounds. Other sources indicate that the size differential was not quite so vast, but still considerable. He even managed to score a knockdown of Wright in route to the ten round decision, securing himself a shot at top-rated contender Jack Sharkey. Sharkey, a clever, tough future Hall-of-Famer, had already been in the ring with the likes of Harry Wills, Jack Dempsey, and Max Schmeling. When they fought on July 22, 1931 at Ebbets Field in New York, Sharkey outweighed Walker by nearly thirty pounds and stood a full five inches taller. Still, the determined Toy Bulldog put on the performance of his life, continually dogging Jack for fifteen rounds. The official result of the match was a draw, which was an impressive accomplishment for the former welterweight in itself. But many at ringside protested that Walker deserved the decision. It was Sharkey, however, who got the title shot. Less than a year after his bout with Walker, Jack Sharkey won a fifteen round decision over Germany’s Max Schmeling to win the heavyweight championship.

Sharkey’s win over Schmeling had been as controversial as the draw with Walker. Thus many hankered for a showdown between Schmeling and Walker, the two men many felt were really the best heavyweights in the world. That fight happened on September 26, 1932 at Madison Square Garden. Again Walker put on a marvelous exhibition of bravery. He took the fight to Schmeling and refused to stop punching. But Schmeling’s size, punching power, and counter-punching technique took their toll as the fight wore on. After failing to put the German away with a valiant last stand in the eighth round, Walker had clearly had enough. His energy sapped he took an horrific battering, prompting many in the crowd to scream for the fight to be stopped. Manager Doc Kearns signaled the referee, who mercifully stopped the fight.

Later Years

After the bloody, bruising beating experienced at the hands of Schmeling, Walker was never again the same fighter. Though he knocked out the massive Arthur De Kuh, who outweighed him by nearly fifty pounds, with a stunning first round knockout, he decided to abandon his dream of winning the heavyweight title. He returned to the light heavyweight division, where he lost in a second go at the championship, dropping a unanimous decision to future Hall-of-Famer Maxie Rosenbloom in 1933. A year later he beat Rosenbloom in a non-title rematch, his final victory over a world-class fighter. After winning just two fights in 1934 and losing four, Walker retired in 1935. At the end of his career, despite being on of the most popular and successful middleweights yet to come along, he was virtually penniless, having blown his fortune on his playboy lifestyle. An unsuccessful acting career was followed by a period as a bar owner and then a traveling salesman. A talented painter (primarily of landscapes) and golfer, he pursued these two hobbies with great passion in his later life.

Mickey Walker, the Toy Bulldog, died on April 21, 1981, at the age of seventy-nine. In 1990 he became part of the inaugural class of inductees into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

Sources

- An Illustrated History of Boxing, by Nat Fleischer and Sam Andre

- A Century of Boxing Greats (1997), by Patrick Myler

- Roberts, James B. and Alexander G. Skutt. The Boxing Register (4th ed. 2006.)

- CBZ Profile: [1]

Factoids

- Walker was his own manager for much of his early career, until Doc Kearns took over. (Walker & Jack Kearns photo)

- On March 23, 1931, in Trenton, New Jersey, he married Clara Hellherm, 20, an amateur artist and etcher, only to learn that his first wife’s divorce was not yet absolute. The divorce was recommended December 19 and should have become final 90 days later. But the court failed to sign the preliminary decree until February 14, putting off the actual divorce to May 14.

- Died April 28, 1981 in Freehold, New Jersey, USA.

- Inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame; the World Boxing Hall of Fame; and the New Jersey Boxing Hall of Fame June 15, 1969.

External Links

MICKEY WALKER, WHO CAPTURED 2 WORLD BOXING TITLES, DIES AT 79

Mickey Walker, who won the world welterweight and middleweight boxing titles and also fought some of the sport’s top heavyweights, died yesterday morning at Freehold Area Hospital in Freehold, N.J. He was 79 years old.

The primary cause of death, according to Dr. L. Glenn Barkalow, his physician, was Parkinson’s disease. The remains were cremated. Nicknamed The Toy Bulldog because of his bristling, aggressive style, Walker’s ring career spanned 17 years, from 1919 through 1935. He weighed between 147 and 170 pounds for his 160 professional bouts, yet fought such prominent heavyweights of the period as Max Schmeling, Jack Sharkey, and Primo Carnera. He was elected to the Boxing Hall of Fame in 1955.

Walker was as colorful and flamboyant as Jack Dempsey and Gene Tunney, his larger-sized contemporaries. It is estimated he earned more than $3 million in the ring, and it is a fact that he spent a good deal of what he earned.

In recent years, after having contracted Parkinson’s disease in 1974, Mr. Walker was confined to several rehabilitation centers and nursing homes in the metropolitan area.

Walker won the world welterweight title from Jack Britton in November of 1922, then lost the title in Scranton, Pa., in 1926 to Pete Latzo.

Later that year Walker won the middleweight title from Tiger Flowers in Chicago in 10 rounds. He held the 160-pound championship until 1931 when he relinquished it in order to move into a higher weight class. Knocked Out by Schmeling

When he moved up, to light-heavyweight, he lost to Tommy Loughran and Maxie Rosenbloom in 175-pound division title fights. Walker also fought Sharkey, a heavyweight who weighed 196 pounds, to a 15-round draw in 1931, then was knocked out in eight rounds by Schmeling, another heavyweight, on Sept. 26, 1932.

In his 160 bouts, he scored 60 knockouts, many with his powerful left hook, and won 33 by decision, with four draws. He lost 11 by decision, three on fouls, five by knockouts. Forty-five more bouts were no decisions, and one was ruled no contest.

Mr. Walker was married six times, twice to Clara Helmers and twice to Maude Kelly. After Mr. Walker retired in 1935, he opened a tavern in his hometown, Elizabeth, N.J. He also took up painting, and had a one-man show at the Associated American Artists Galleries on Fifth Avenue in April of 1955. There were portraits, landscapes and abstracts – 19 canvases in all. Ring Forges Philosophy

Of his art, he said: ”There’s not much difference between prizefighting and painting. It’s just a matter of time. As a youth I could express myself with my fists. Physical expression belongs to youth. Then the years go by. I found art -and expression – in colors.”

”A lot of my philosophy comes from the ring,” he added. ”You learn in life there are always the ups and downs. We must have enough sense to enjoy our ups and enough heart to get through our downs.”

Edward Patrick Walker was born July 13, 1901, in the Keighry Head section of Elizabeth. He was dropped from the Sacred Heart Grammar School after eight years. Then, after his father had ”whaled the daylights out of me,” he went to work in the architectural office of George B. Post & Co. He also attended the Mechanics Institute in the evenings. ”It was the lowest period of my life,” he said.

When World War I broke out, Walker was too young to enlist; so he went to work, first as a riveter in an Elizabeth shipyard, then at a Staten Island shipyard.

At the shipyard, Walker got into a fight with Eddie McGill, a professional boxer unknown to Walker. Walker floored the professional with a decidedly unamateurish left hook. They fought for 25 minutes with an audience of 5,000 workers who had left work to view the fight. Walker was given the unanimous decision – and his notice from the company.

But after that he decided to become a professional boxer. Travels With Kearns

He joined with Jack Kearns, the manager who had split with Jack Dempsey, and the pair traveled through the United States and Europe for nine years.

When Walker fought a British contender in London in June of 1927, Kearns promised that the two would visit Ireland after the fight. Walker’s purse was $120,000, and Kearns bet it all at odds of 4 to 1 and won.

When Walker knocked out Tommy Milligan, the European champion, Kearns and Walker collected more than $600,000. Mr. Walker is survived by his wife, Martha Chudy Walker, of New York, and brother, Joseph, of Bricktown, N.J. He has three sons by his previous marriages, Michael Jr., Kerry and James. A daughter, Patricia, died 12 years ago.

Illustrations: Photo of Mickey Walker

Boxing Record: Mickey Walker